We recently sat down with Taylor Roakes, CSP to discuss her passion for human and organizational performance (HOP) and its role in driving EHS outcomes. Read on to learn her insights on the benefit of using HOP in safety to build a stronger health and safety program.

About Taylor Roakes

Taylor Roakes is a Safety Engineer at the LyondellBasell Louisiana Integrated PolyEthlyene Joint Venture in Lake Charles. She has more than 8 years of professional experience in the field. Her initial interest in EHS came from her mom, an environmental attorney, and her aunt, an EHS manager.

In college, Taylor studied at the University of Findlay’s Environmental, Safety, and Occupational Health Management program. She completed co-ops in steel manufacturing, refining, and food manufacturing. After graduation, she worked as a safety specialist at paper mills for four years until she accepted an EHS role in the petrochemical sector.

Applying HOP in Safety

Taylor’s first learned about human and organizational performance in 2018 when she was a safety specialist in the paper industry. While there, she had the opportunity to meet and learn from HOP thought leader Dr. Todd Conklin.

Ever since, she’s found endless ways to integrate HOP principles into different manufacturing locations. Her experiences show how you can apply HOP in safety to build better relationships and find solutions to everyday problems.

1. What’s your quick definition of HOP to anyone who needs a refresher?

HOP is the way people, work systems, culture, processes, and equipment interact. The five HOP principles are:

- Error is normal and likely.

- Blame fixes nothing.

- Systems drive behavior.

- Response matters.

- Continuous learning is essential.

2. What’s an example of how you’ve applied the principles of HOP to solve an issue or improve a process?

I intentionally use HOP principles every day, both at work and at home. Through building relationships and earning others’ trust in the workplace, I try to learn about how work actually happens in the field.

A good example of how I’ve applied this is with highly dangerous processes. Take the process of threading up a paper machine in a paper mill as an example. This is a high-risk task that requires people to interact closely with energized, rotating equipment.

After observing and talking to the people doing the task, I can recommend a safer approach. Having our team thread the reel section of the machine at an alternative location away from the in-running nip point, for examples, allows us to distance people from the hazard. This is an application of Dr. Conklin’s statement that: “Workers are not the problem. Workers are the problem solvers.”

3. Thinking back on your EHS career so far, what are some of the ways that you think teams fail to recognize the human component of health and safety performance?

I’d challenge my peers in EHS to spend an hour tallying up how many times they make an error. According to Los Alamos National Lab, people make an average of 5 errors per hour. And while most of these mistakes don’t result in a negative outcome, you never realize their impact until after they’ve happened.

From my personal experience, I believe that industry and manufacturing still need to accept and embrace the first HOP principle that error is normal and likely. We’re all human and make mistakes every day.

4. Do you actively practice HOP every day, or do you think it’s something that becomes second nature over time?

HOP has become a way of living and thinking differently for me over the years; however, there are situations where I must intentionally pause, collect my thoughts, and then respond. Most of the time, this happens when we’re discussing an event, and others want to place blame rather than learn about the situation.

As Walt Whitman said, “Be curious, not judgmental.” Workers make decisions that make sense to them at that time. They also react similarly to the same stimuli. In other words, if one person makes an error, the next person will likely make the same error given the same environment and information. That is, of course, unless we fix the system.

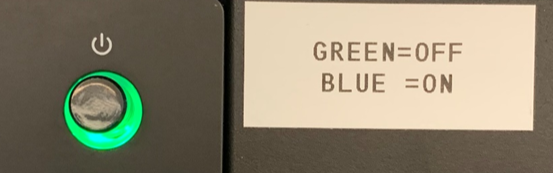

For example, at work, we have a speaker system with a blue light to indicate that it’s on and a green light to indicate that it’s off. How many times would you guess people think the speaker is on because the light’s green? It has happened so many times that someone put a sticker on it (pictured), and people still can’t figure it out. Bottom line is this: if the system doesn’t support our desired outcome, then we shouldn’t blame workers for making an error.

5. How has understanding HOP helped you grow as an EHS professional?

HOP has made me a better active listener which has helped me grow as both an EHS professional and an overall human being. I do this by asking open-ended questions to improve learning within the organization. It can be as simple as asking TEDS questions:

Tell me. Explain to me. Describe to me. Show me.

I also like to use the 4 Ds: dumb, dangerous, difficult, and different. Putting the two strategies together, I might say to an employee: “Tell me about something you have to do that’s difficult.” In my experience, using these phrases allows me to get more information from employees than simply asking “why” over and over.

6. How has HOP changed the way you approach problems in health and safety?

Health and safety professionals in industry can have a bad reputation as being the “safety cops.” But I’ve found that when we apply HOP in safety, we can establish relationships, build trust, learn about how work actually happens, and work together to build capacity in our systems that allows workers to fail safely. The goal for EHS professionals should always be to make the right way the easy way.

7. In your experience, how can HOP help improve the quality and outcomes of EHS programs and initiatives?

HOP helps you get buy-in for EHS programs. One of the main initiatives of HOP is to set people up for success and make it easier to do work. When you involve, value, and use the worker’s input, then they’re more likely to participate.

At the paper mill, for example, there was a pulp dryer from the 1950s that was very difficult to operate. I spent time talking and watching workers use the dryer. One day, someone came up with an idea to add brackets to prevent the rollers from creating a pinch point. This machine guarding was effective because it eliminated the hazard while still allowing people to perform the work they needed to in this area. After we installed the brackets and verified that they worked, workers continued to come up with ideas to try.

8. What do you want EHS professionals to understand better about HOP?

The HOP principle, blame fixes nothing, is so important for EHS professionals to understand and apply. When we observe something that’s either unsafe or deviates from policy, the way we respond determines how people approach us going forward.

We have to remember that EHS is a support group for operations. Companies are in business to operate and make a product. I truly believe that people are trying to do their job as safely and efficiently as possible, and so I try to treat everyone with kindness and ask them non-judgmental questions about their work.

When you express curiosity, rather than judgement, it allows the person doing the task to see where you’re coming from and think about the task from a different perspective. You know you’re making a difference when your frontline workers come to you to ask for help or share their ideas.

9. What would be your advice to someone who wants to implement a HOP-based approach but doesn’t know how to get started?

Just try it! Take time to get to know the people you work with on a personal level and build relationships. After you earn their trust, dedicate time to learn and understand how work gets done.

You can learn a lot from observing “successful” work. By successful, I mean there is no bad outcome. This doesn’t mean that no one missed a step or deviated from the procedures. Todd Conklin calls this the “black line” (work as expected in a procedure) and the “blue line” (work as performed). Learning the way work actually happens can help you improve systems, prevent future events, and implement effective defenses.

Taylor’s Resource Recommendations

Of course, we had to ask Taylor about some of her favorite professional development resources. Check out her recommendations below!

HOP in Safety Resources

- Understanding Mental Models by Rob Fisher

- Pre-Accident Investigations by Todd Conklin

- Bob’s Guide to Operational Learning by Bob Edwards

- HOP Hub (a free online resource)

Professional Development in Safety

There’s so much untapped value in networking and joining professional associations. Two of my favorites are the American Society of Safety Professionals (ASSP) and American Fuel & Petrochemical Manufacturers (AFPM).

Taylor’s top professional advice to her fellow EHS practioners:

Be kind. Listen to understand (not respond). Be curious and approachable. Keep your promises.